The Spirit Engraved at the Tip of the Brush – The Two Faces of Handwriting: Ahn Jung-geun and Itō Hirobumi

By Koo Bon-jin (Lawyer & Handwriting Analyst)

A person may wear a mask, but handwriting cannot. Strokes are the heart itself; brush lines are the flow of the spirit. Political rhetoric and embellishment fade over time, but writing left on paper reveals the human interior without deception. Words and actions can be staged, but the letters that flow naturally from the fingertips are the instinctive trace of a person, preserving the very patterns of their character and spirit.

In that sense, the handwriting of two figures who stood at the historical crossroads of East Asia in the 20th century—Ahn Jung-geun and Itō Hirobumi—is far more than a collection of calligraphic works. It is the residue of their spirit and their age. Their scripts are visual emblems of two divergent worldviews, the inner structures of two souls shaped through the medium of the brush. Within each written line, in every stroke of every character, is not only meaning but also the spirit of the era and the imprint of personality. Handwriting is at once historical record, portrait, symbol, and testimony.

To the naked eye, their scripts differ sharply. Yet the difference is not merely a matter of taste or style. One man’s hand preserves the tautness of a “vertical spirit”; the other’s bears the traces of a power-centered ego, marred by instability and deviation. This contrast at the tip of the brush speaks directly to the decisive differences in their lives and choices. The gap in spirit and aesthetics mirrors the divergence in their historical paths—and all of it is etched in their brushwork.

Restrained Resolve – Ahn Jung-geun’s Brush

Ahn Jung-geun’s handwriting is, in a word, the epitome of restrained resolve. Thick and upright strokes, calm yet unyielding execution, and forms that are both orderly and resolute. This is not the product of artistic instinct alone—it is the visible form of a belief and discipline that rise from within. It is the embodiment of what might be called psychological verticality. The condensed energy and tension in each stroke cannot be achieved through mere practice or flair.

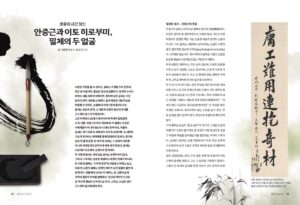

The direction of each line is precise; its angles are alive; each character maintains structural balance. The brush pressure is even and consistent, harmoniously weaving contrasts between tension and release. This reflects emotional control, a clear sense of purpose, and the unity of thought and action. Each character stands as if an armed soldier holding its position—revealing Ahn’s inner order and the steadfast center of his convictions. In particular, the inscriptions he left in prison—such as “Success depends on Heaven” (成事在天) and “The mountain’s colors are the same in ancient and modern times” (山色古今同)—embody an unshaken faith and composure even in the face of death. The brush carries emotion without excess, and reason without dryness.

His script is not simply “good calligraphy.” It is the sculpture of belief, the evidence of cultivated discipline, the final record of how a man lived and how he met death. After the Harbin assassination in October 1909, while imprisoned at Lüshun, Ahn produced many calligraphic works—most of which went to Japanese officials. High court judges, prosecutors, clerks, police, and military officers lined up to request his handwriting, and he never refused. Their desire was not mere political ritual; even his adversaries were moved by his composure, eloquence, and dignity in speech and bearing.

From a calligraphic standpoint, Ahn’s writing follows the tradition of the Yan Zhenqing style. His strokes are thick and precise, adhering faithfully to the rule of “hiding the head and protecting the tail” (藏頭護尾). In the balance of tension and relaxation, the harmony of force and restraint, the strength of brush pressure and clarity of structure—there is a depth beyond technique. It is the condensation of Ahn Jung-geun’s very character into writing.

Anxious Display – Itō Hirobumi’s Brush

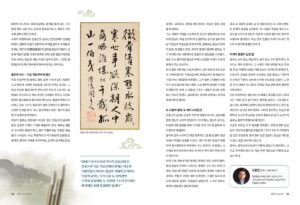

At first glance, Itō Hirobumi’s handwriting also appears forceful. The strokes are large and rapid, showing attempts at refined brushwork. Yet on closer examination, a different picture emerges. The direction of lines wavers; the proportions of strokes are inconsistent; spacing between characters and lines lacks balance. Brush pressure fluctuates excessively, and the sizes of characters vary, leaving an overall impression of restlessness and disorder. In handwriting analysis, such traits are often interpreted as signs of psychological imbalance.

Unlike Ahn’s writing, where reason governs emotion, Itō’s reveals emotional turbulence. At times, hastily executed cursive forms appear; in some works, brush movements verge on theatrical. This reflects an impulsive, self-expressive temperament—and can also be read as the reactive psychology of a man trying to assert authority. His desire to wield power even through writing often disrupts harmony.

Though he experimented with calligraphic technique, he failed to achieve spiritual unity. His emphasis and distortion of strokes may aim to suggest dynamism, yet without an anchoring center they drift. Structural disorder and lack of control hint at a leader inwardly unsettled. Outwardly large and strong, his script is inwardly weak and blurred—that is the impression Itō’s hand leaves.

In his time, Itō’s calligraphy circulated as a legacy of a high-ranking statesman. Yet its market value relied more on his name than on artistic merit. As Japan’s first prime minister and a symbol of modernization, his handwriting carried a certain historical price tag, but its internal structure and content fell far short of genuine calligraphic achievement. Even his writing was but another shell of political power.

Two Scripts, Two Spirits of an Era

Ahn Jung-geun’s script is more than personal handwriting—it is the visual form of devotion to a community. Self-assurance, vertical spirit, restrained consideration for others—all find expression at the tip of his brush. The spaces between characters are measured, each line breathes independently in its own cadence. It is as though a single mind extends itself across the paper in disciplined order. His script is the contour of a spirit, the shape of a character engraved in ink.

By contrast, Itō Hirobumi’s handwriting reveals exaggeration of authority, psychological unease, and loss of center. Instead of clear structure, it offers scattered momentum and disordered form—traits of a mind lacking consistency. His hand held strength, but not order; the breadth of his strokes concealed the tremors within.

Ultimately, their handwriting symbolizes their spirits, the directions of their societies, the collision of two civilizations. One man faced death with his spirit standing upright; the other, in life, let even his strokes scatter horizontally. This is not merely a difference of men, but of histories—and of trajectories.

The Final Word Left by the Brush

Handwriting is a voice without sound. It is the trace of the living, the testament of the departing. It tells more honestly than words what a person thinks, believes, and how they have lived. Facing imminent death, Ahn Jung-geun took up his brush and left the words “Korean National Ahn Jung-geun” alongside his inked handprint. This was no mere signature—it was a solemn oath to the nation and to Heaven.

Itō Hirobumi lived to serve four terms as prime minister, but in death left behind little more than the remark, “Foolish fellow!” His writing, though outwardly graceful, lacked an inner core; his brush danced, but his spirit was scattered. The truth testified by history is clear: one man’s script remains the model of a nation; the other’s survives as fragments of power.

Even now, we stand before these two hands. Which reveals the true spirit? Which holds the beautiful heart? What must we remember? The lines on paper speak: the spirit does not sink, the soul does not fade. Handwriting endures to bear witness to how you lived—and asks you in return: With what heart are you living now?

(The Great Korean, Ahn Jung-geun” No. 590)