Seo Sang-ryeol (1854–1896) was an early leader of the Korean resistance movement against Japanese occupation, known for his active participation in the Jecheon Righteous Army in 1895, where he played a key role as the vanguard commander. He studied under Kim Pyeong-muk and Yu Jung-gyo, succeeding the Hwa-seo School of Confucianism. With a firm belief in the righteousness of Confucian principles, he fiercely opposed Japan’s encroachment on Korea’s sovereignty.

Born in Danyang, Chungcheongbuk-do, Seo Sang-ryeol came from a prominent family. His father, Seo Je-sun, held the title of Tongdeokrang, and his mother was from the Pyeong-pa Yun clan. His courtesy name was Gyeongam, and his pen name was Chunsudang, with his ancestral home in Dalseong. Known for his intelligence and integrity from a young age, he passed the military service exam and served as Seonjeongwan (an official role), earning recognition for his writing skills.

Seo Sang-ryeol strongly adhered to the principle of “rejecting foreign influence and protecting Confucian values.” He studied under Kim Pyeong-muk and later moved to Cheongpung, inspired by Yu Jung-gyo, to pursue learning and to strengthen his dedication to Confucian ideals. He eventually led the intellectual and righteous movement in the Jecheon region.

When the Gapsin Coup (1884) and the Gabo Reform (1894) occurred, Seo fell ill with distress over the country’s situation. The decree to change traditional clothing in 1894 particularly shocked him, and he initially sought to raise a Righteous Army but was persuaded to delay his plans by Yu In-seok. After the assassination of Empress Myeongseong in the Eulmi Incident (1895), he wept for nine days and once again attempted to raise a Righteous Army, though with limited support.

In 1895, after the imposition of the topknot-cutting decree, Seo returned to Jecheon, where he joined forces with Yi Chun-young and An Seung-woo, based on Kim Baek-seon’s hunters. They soon entered Jecheon with their army. Although Seo was offered leadership, he humbly deferred to Yi Pil-hee and instead became a military advisor, reflecting his Confucian ideals of loyalty and service without seeking power.

In the following months, Seo led several successful skirmishes, including one at Janghoehyeop. He helped to reorganize the forces in Jecheon and supported the larger Righteous Army movement in the region. By 1896, he had gathered a force of around 3,000 men and led a notable attack on Japanese military supplies in Sangju. However, despite his efforts, Seo’s forces struggled due to a lack of modern weaponry and experience.

In February 1896, Seo’s army was attacked by government forces and suffered significant losses. He retreated to Jecheon and continued to defend the region under Yu In-seok’s command. In the summer of 1896, while attempting to expand the Righteous Army’s reach to the northern provinces, Seo’s troops were ambushed near Hwacheon. After a fierce battle, Seo was killed in action on June 13, 1896.

Seo’s comrades and disciples honored him with memorials, praising his loyalty and dedication to righteousness. He was remembered as a man of unwavering integrity who chose a noble death over a dishonorable life. In recognition of his contributions, the South Korean government posthumously awarded him the Order of Merit for National Foundation in 1963.

Seo Sang-ryeol was a scholar who transformed his Confucian ideals into action, standing as a leading figure in the early Korean resistance movement. His commitment to righteousness and his role in the anti-Japanese struggle left a lasting legacy in Korea’s history of independence.

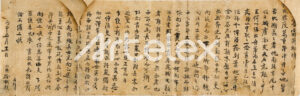

Translation:

The rainy season has finally cleared, and I find myself deeply concerned about whether Commander Gil-su is well and if there are no significant threats in the camp. For several days, our forces in the south have been clashing with the barbarians, facing dangers from arrows and stones. How could we ensure that our troops are well-protected and avoid any harm in such perilous conditions?

As I lay ill in the mountains, my worries never cease, and it is difficult to suppress the overwhelming anxiety that consumes me day and night. Fortunately, my health has somewhat improved, and I have reached the borders of Yeongwol, where I met General Kim Tae-won. Hearing the detailed circumstances from him brought me comfort and filled me with joy. However, I’ve heard that Bu-gwang (a person’s name) has already arrived in Sinlim, and now I wonder whether we should head to Jecheon-eup to establish a camp or advance to Jucheon, pass through the eastern mountain passes, and set our sights westward.

Camping in Jecheon appears weak, making it difficult to command our forces effectively, while advancing westward offers us more flexibility. What do you think would be best? The most pressing concerns for the military are provisions and supplies, while weapons are the most crucial assets. If it proves difficult to procure these in Jecheon, we could also seek them from the west. The advantage of planning in the west is that it requires no special wisdom, and thus, it will align with the thoughts of everyone.

Recently, I have been wondering how things are progressing. Once a grand strategy is set, one must not allow short-term comfort or minor advantages to shake their resolve or alter their purpose. I hope that you will not ask others for further input, but instead, trust in your initial instincts, take command, and immediately deploy the troops. If we join forces with our friends in Silgok and Haeseo, cross Yangmaeng (a place), and occupy a terrain more secure than even a river, there should be no doubt of success.

Woo Pil-gyu and Oh Sa-won have already been dispatched to the region of Pyeong (presumed to be a place), and the recruits and scattered troops are awaiting my orders to join at the camp in Chuncheon, firmly committing to march westward together. I have already explained this reasoning in great detail in my previous letter. I hope you will consider it. A courier has arrived, but I received no clear instructions in your letter, which has left me feeling both frustrated and puzzled. I shall leave it at that and extend my regards.

12th day of the 5th month, Year of Byeongsin,

Major Seo Sang-ryeol, respectfully bowing.