Lee Seong-ryeol (1865 – unknown) was an official during the Korean Empire who served in various high-ranking positions, including Chief of the Imperial Household, Minister of State, and Special Advisor to the Imperial Household. His family originated from Yean, and his pen name was Toeam. He was born in Anseong, Gyeonggi Province, as the son of Lee Sang-hoon and was later adopted by Lee Sang-yu.

In 1888, during the 25th year of King Gojong’s reign, he passed the special state civil service examination and began his career in the Hongmungwan (Office of Special Advisors). The following year, as a senior officer, he led the drafting of petitions in the Hongmungwan and subsequently held positions such as Jikgak in the Gyujanggak (Royal Library) and a lecturer in the Office of Crown Prince Education. He also briefly served as a Senior Scholar at Sungkyunkwan but was exiled due to administrative issues, though he was soon reinstated.

In 1894, he was appointed as the Jeolla Province’s grain transport officer, responsible for overseeing the transportation of taxes in kind. However, with the implementation of monetary taxation following the Gabo Reforms, he was dismissed from his post. He later held several key positions, including Governor of Jinju, and was bestowed with honorary titles such as Royal Secretary and Minister of the Interior.

During the 1895 assassination of Queen Min, he served as the steward of the royal funeral. He was later appointed as a memorial officer for the posthumous rites of Queen Min and was subsequently assigned as Governor of Gyeongsangbuk-do. In 1898, he was appointed as a first-class official in the Jungchuwon (Privy Council) and was sent on diplomatic missions to Russia, France, and Austria. He also briefly held the role of Deputy Minister of Finance.

In 1900, he became the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and although he was reappointed as Governor of Gyeongsangbuk-do, he expressed his desire to resign multiple times, ultimately leading to his dismissal. In 1903, he returned as Governor of Gyeongsangbuk-do and later as Governor of Jeollabuk-do, but due to administrative delays, he was again dismissed.

In 1904, he served as Chief of the Imperial Household and later as Special Advisor to the Imperial Household. When the Emperor decreed changes to traditional court attire, he submitted a petition opposing the reforms, supporting the argument made by Choi Ik-hyun to preserve Korea’s traditional customs.

After the signing of the Eulsa Treaty in 1905, Lee received a letter from Choi Ik-hyun urging him to take part in the movement to resist Japan and restore national sovereignty. He soon resigned from office and retreated to Yeoju, where he collaborated with figures like Min Jong-sik and Lee Si-yeong to organize the Righteous Army and raise funds for the cause. However, when the Japanese military confiscated the Righteous Army’s list of members, leading to the capture of many, Lee deeply regretted his failure and ultimately took his own life through a hunger strike.

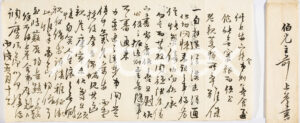

Translation:

Since the day I bowed and departed, I have been unable to send any communication, leaving me with a deep sense of sorrow and an even stronger yearning. However, receiving your previous letter brought me great joy and comfort, which remains with me still. During this time, I wonder if the weather has been favorable for your parents, and if you and your spouse have remained in good health. I bow before you with deep longing and offer my best wishes. I trust that you continue your studies diligently as before, and that the young one is growing increasingly bright and promising. All of these things weigh heavily on my mind. How have you been managing your responsibilities, attending to those above you and keeping those below you at ease?

As for me, I have been eating well and living comfortably without any significant hardships. However, I am deeply ashamed and troubled that I have caused worry for my elderly parents and have not been able to properly care for my household. I find myself at a loss for words about the future, and even though my current circumstances are difficult, I wonder if I can find no way to manage things, even if it means borrowing to get by.

Recently, I was caught up in forced labor and had to carry burdens as far as Geumseong. The sight of such misery and hardship makes me reflect on the fleeting nature of life, which moves as swiftly as clouds, leaving no time to pause. I can only find relief in knowing that, fortunately, things at the government office remain unchanged from before. I will leave it at that without further elaboration and send this brief reply.

Your younger brother, Seong-ryeol.

This is the high-level English translation of your letter, refined for tone and style.