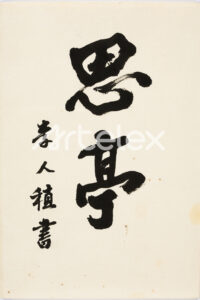

李人稙, (1862 –1916) was a prominent figure during the Japanese colonial period, known for his work as a journalist, novelist, and playwright.

He made his mark on Korean literature by writing “Tears of Blood”, considered the first modern novel in Korea. In 1907,

One of the most controversial aspects of Lee’s life was his role in facilitating the **Japan-Korea Annexation**. On August 4, 1910, he traveled to Japan on behalf of Lee Wan-yong, who lacked proficiency in Japanese, to negotiate with Komatsu Midori, the Chief of Foreign Affairs at the Residency-General. His intermediary role proved crucial in the annexation process, which culminated on August 22, 1910, when the treaty was signed.

Following the annexation, Lee became a prominent collaborator with the Japanese colonial government. He was deeply involved with the **Kyung-hakwon** (Academy of Confucian Studies), where he edited **Kyung-hakwon Magazine** to promote ideologies that justified the annexation. Furthermore, when Emperor Taisho ascended to the throne, Lee composed a tribute to the Japanese emperor, further solidifying his loyalty to Japan. Upon his death in 1916, the Japanese Governor-General’s Office recognized his contributions by providing his family with a funeral subsidy, acknowledging his significant role in supporting Japan’s imperial ambitions.