Jeong In-bo, born in 1893 in Seoul, was a renowned scholar, historian, journalist, politician, and writer in Korea during the late Joseon Dynasty, the Japanese colonial period, and the early Republic of Korea. His life and work were deeply rooted in the preservation of Korean culture and history, especially during the turbulent era of Japanese occupation. He was from the Dongrae Jeong clan, and his pen names included “Wuidang” and “Damwon.”

Jeong’s early education was shaped by his grandfather and family members who were steeped in Confucian scholarship. He was particularly influenced by scholars of the Yangming School of Confucianism, including Lee Geon-seung. In 1908, at the age of 16, he traveled to Shanghai, China, where he spent two years, engaging with Chinese scholars and contributing to Korean independence activities. This period marked the beginning of his lifelong dedication to Korean cultural preservation.

Upon his return to Korea, Jeong became a professor at Yonsei University in 1922, teaching Korean literature and Chinese classics. His lectures were well-received, earning him teaching positions at other prestigious institutions, such as Ewha Womans University and Seoul National University. During this time, Jeong established himself as a leading figure in Korean studies, focusing on the works of notable Korean scholars like Dasan Jeong Yak-yong and Shin Chae-ho. His research contributed significantly to the fields of Korean history and philosophy.

Jeong was also active as a journalist, serving as a columnist for Dong-a Ilbo, where his sharp, fearless critiques gained widespread recognition. His writing extended to poetry, particularly in the traditional sijo form, where he created numerous works that resonated with readers during and after the colonial period. He published important works, including **”Chosun History Studies”** and **”Damwon Sijo Collection,”** which remain influential in the study of Korean literature and history.

Following Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, Jeong played an important role in the newly formed government. He was appointed the first Chairman of the Audit Committee, responsible for overseeing government accountability. However, political conflicts with President Syngman Rhee’s administration led to his resignation in 1949.

Despite the political tensions, Jeong continued his scholarly work, dedicating himself to restoring Korean cultural pride. His efforts were aimed at ensuring that Korea’s unique cultural heritage remained intact and appreciated in the post-colonial era.

Unfortunately, during the Korean War in 1950, Jeong In-bo was abducted by North Korean forces. His exact fate remains unclear, though it is believed he died later that year. His contributions to Korean history and culture were recognized posthumously when he was awarded the Order of Merit for National Foundation in 1990. His collected works have been published, and his intellectual legacy continues to shape Korean historical and literary studies.

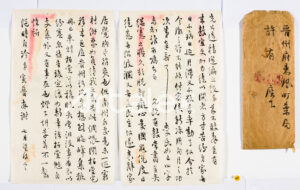

Translation:

I cannot decline the task of selecting and compiling my late father’s posthumous works out of a sense of duty, and since you have repeatedly entrusted this to me, it is only right that I should exert myself even further to accomplish it. However, these days, my heart has been unsettled and troubled, and both I and my family have been plagued by illness without a single day of respite. As a result, I have delayed matters day by day and even for months, and the manuscripts have not been thoroughly reviewed. For this reason, I cannot send them with this dispatch. I shall wait for a cooler season, and within a month’s time, I will devote myself to the task and fulfill your request as desired.

As for the four characters, “愛民如己” (Love the people as oneself), though I do not know who made the request, since you have already given your instructions, I shall naturally write it as requested. Regarding the position of 総憲 (High Censor), I have long wished to relinquish the title, but in my foolish concern for the country, I continued my efforts, causing only endless upheavals. Furthermore, since it brought no benefit to the livelihood of the people, I submitted my resignation and have been residing at home, feeling a refreshing sense of clarity within. Yet, I regret not being able to make even a single inspection tour of the remote regions of the southern towns (南州) and fear that I may have failed the expectations of those in secluded villages who counted on me.

I hear that Master 백당 (Baekdang) has moved to a house near the town, so I can well imagine the state of affairs in Jinju. I understand that the compilation of the “회봉집” is now complete, which surely brings peace of mind to Master 백당. Though you faced many difficulties in your labor, now that the work is suddenly finished, it must bring you a renewed sense of satisfaction. I ask you, please let Master 백당 know if there is any further work beyond the publication of the collection. Writing hurriedly by lamplight, I fear I have left out countless matters, but I trust you will consider them in due time. I pray that you continue to treasure yourself in all things.

With utmost respect, written in reply by Jeong In-bo on the seventeenth day of the seventh month.